🕊️ Introduction: Mahatma Gandhi – The Soul of India’s Freedom.

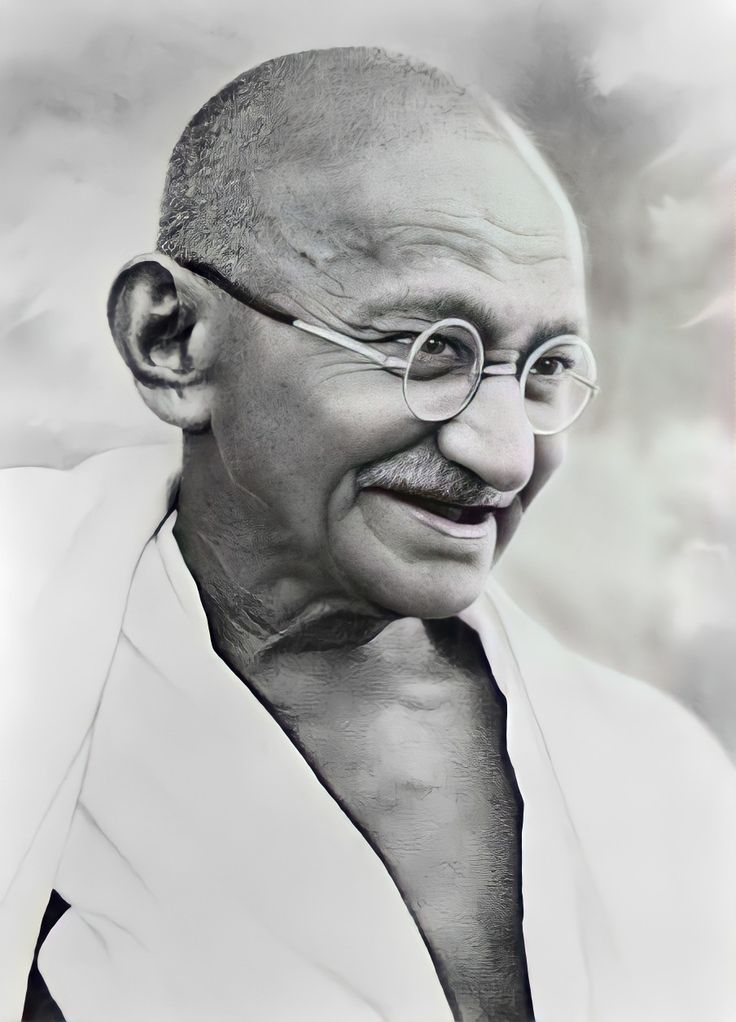

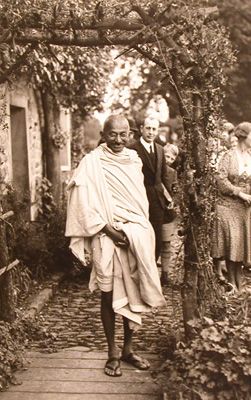

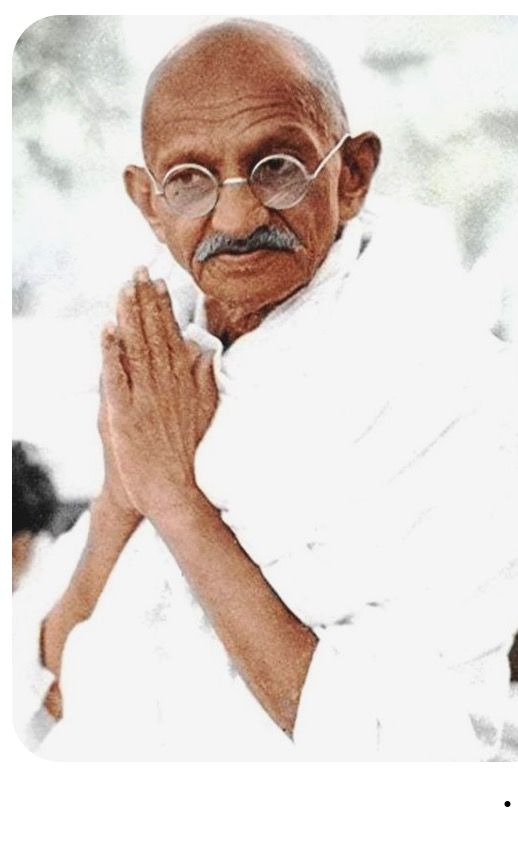

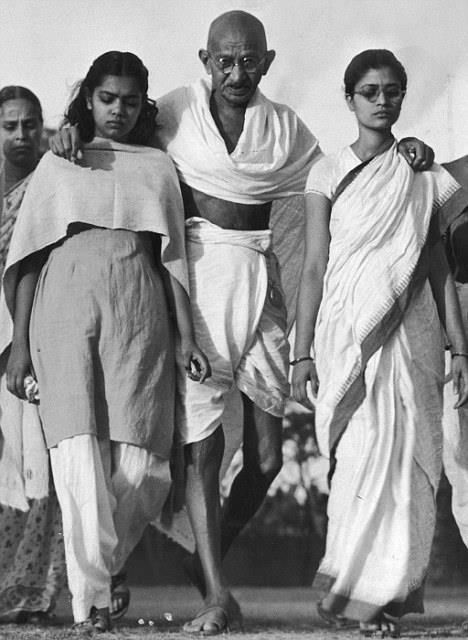

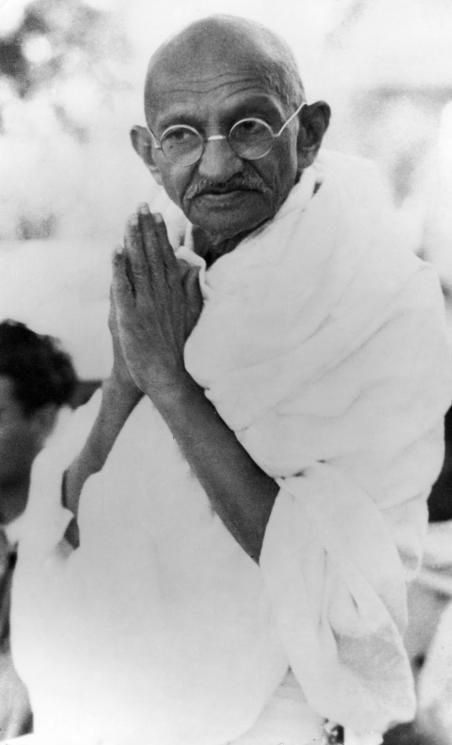

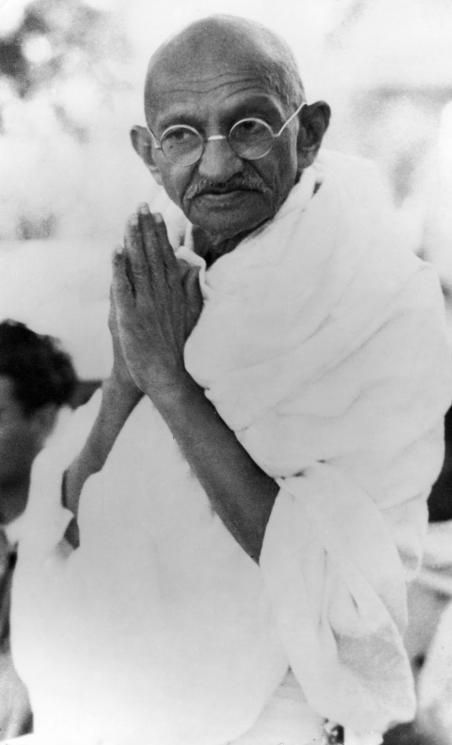

In the vast tapestry of India’s history, few figures shine as brightly and enduringly as Mahatma Gandhi. Revered as the Father of the Nation, Mahatma Gandhi was not merely a political leader—he was a spiritual force, a moral compass, and a revolutionary who redefined the meaning of resistance. His life, spanning from 2 October 1869 to 30 January 1948, was a testament to the power of truth, non-violence, and unwavering conviction.

Born as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in Porbandar, Gujarat, Mahatma Gandhi emerged from modest beginnings. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as the Diwan of Porbandar, while his mother, Putlibai, instilled in him deep religious values rooted in Jainism and Vaishnavism. These early influences shaped Mahatma Gandhi’s lifelong commitment to simplicity, compassion, and moral integrity.

As a child, Mahatma Gandhi was shy, introspective, and curious. He married Kasturba Gandhi at the age of 13, a union that would later become a cornerstone of his personal and political journey. His early education was unremarkable, but his character was already forming around the principles that would later guide a nation.

In 1888, Mahatma Gandhi traveled to London to study law at the Inner Temple. This journey marked the beginning of his transformation. In England, Mahatma Gandhi struggled with cultural adaptation, dietary restrictions, and identity. Yet, it was here that he encountered the Bhagavad Gita, a text that profoundly influenced his philosophy. The teachings of Leo Tolstoy, John Ruskin, and Henry David Thoreau further shaped Mahatma Gandhi’s ideas on civil disobedience and ethical living.

After returning to India briefly, Mahatma Gandhi moved to South Africa in 1893 to work as a lawyer. It was in South Africa that Mahatma Gandhi experienced racial discrimination firsthand—most notably when he was thrown off a train for refusing to move from a whites-only compartment. These humiliations ignited a fire within him. Mahatma Gandhi began organizing the Indian community, founding the Natal Indian Congress, and pioneering the concept of Satyagraha—nonviolent resistance rooted in truth.

Mahatma Gandhi’s 21 years in South Africa were transformative. He led protests against unjust laws, endured imprisonment, and refined his philosophy of peaceful resistance. By the time he returned to India in 1915, Mahatma Gandhi was no longer just a lawyer—he was a leader with a vision.

Back in India, Mahatma Gandhi was welcomed by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who advised him to travel across the country to understand its soul. Mahatma Gandhi did just that. He walked through villages, listened to farmers, and immersed himself in the lives of ordinary Indians. What he saw was poverty, injustice, and colonial exploitation. Mahatma Gandhi knew that India’s freedom would not come from elite negotiations—it had to rise from the grassroots.

In 1917, Mahatma Gandhi led the Champaran Satyagraha, supporting indigo farmers against British landlords. This was followed by the Kheda Satyagraha and the Ahmedabad Mill Strike, where Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership proved that nonviolence could be a powerful weapon. His fame spread, and soon, Mahatma Gandhi became the face of India’s independence movement.

The Non-Cooperation Movement of 1920 marked a turning point. Mahatma Gandhi urged Indians to boycott British goods, institutions, and honors. He promoted Khadi, the spinning wheel, and self-reliance. Mahatma Gandhi’s message was clear: freedom begins with self-respect. His leadership inspired millions, and even when the movement was suspended after the Chauri Chaura incident, Mahatma Gandhi’s influence remained unshaken.

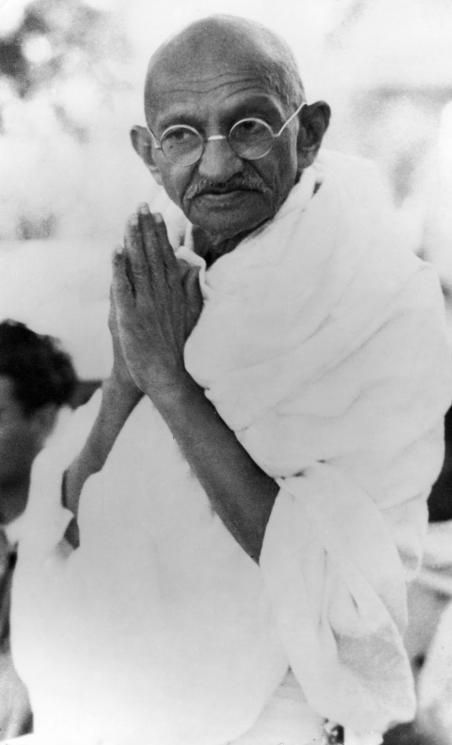

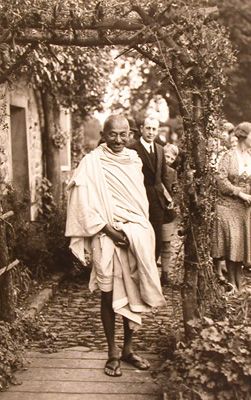

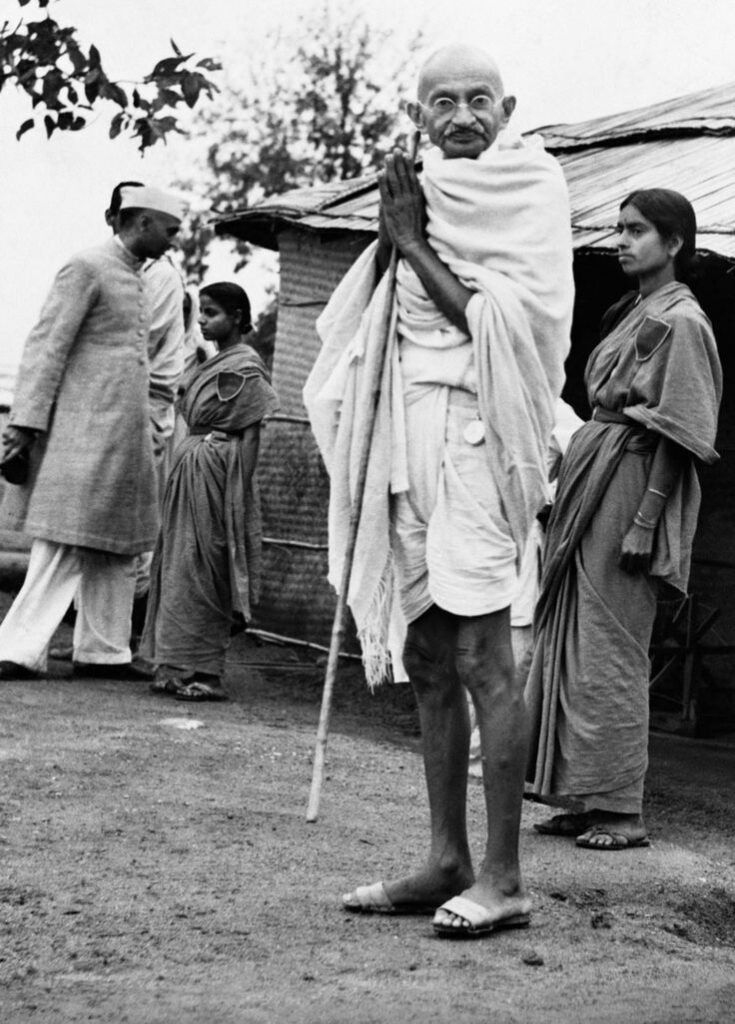

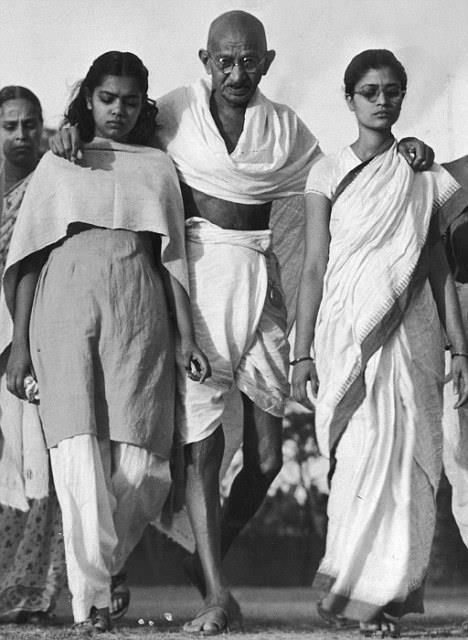

In 1930, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Salt March, a 240-mile walk to Dandi to protest the British monopoly on salt. This act of civil disobedience captured global attention. Mahatma Gandhi’s image—frail, determined, walking with a stick—became a symbol of resistance. The world watched as Mahatma Gandhi challenged an empire with nothing but truth and courage.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Mahatma Gandhi continued to lead with conviction. He opposed untouchability, promoted Hindu-Muslim unity, and supported women’s rights. His Quit India Movement in 1942 was a bold call for immediate independence. Though arrested and imprisoned, Mahatma Gandhi’s spirit never wavered.

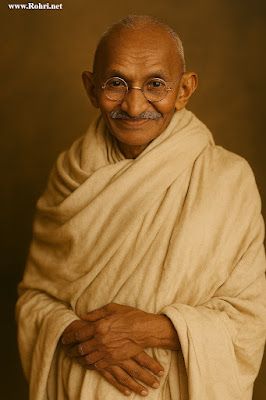

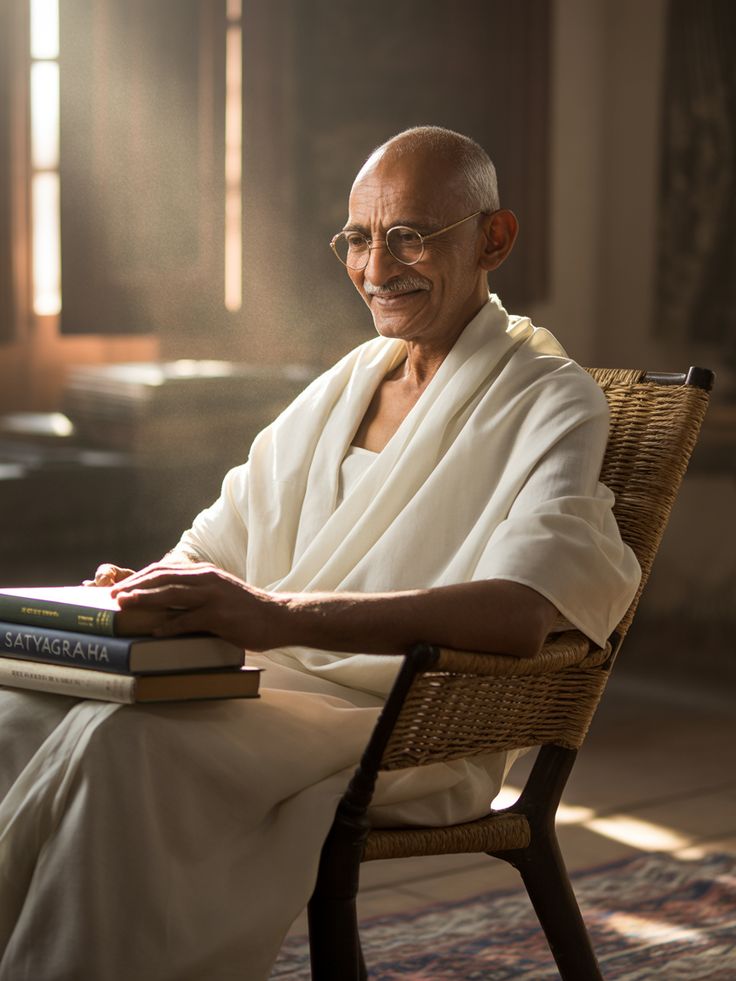

Mahatma Gandhi’s personal life mirrored his public philosophy. He lived in Sabarmati Ashram and later Sevagram, wore simple clothes, and practiced fasting as a form of protest and purification. His relationship with Kasturba was one of mutual respect and sacrifice. Mahatma Gandhi’s experiments with truth, celibacy, and diet were controversial but deeply personal.

As India approached independence, Mahatma Gandhi’s role became even more critical. He opposed Partition, fearing communal violence. In the wake of riots, Mahatma Gandhi walked through the streets of Noakhali, preaching peace and unity. His final fasts were aimed at healing a wounded nation.

On 30 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse in New Delhi. The nation mourned. The world wept. Mahatma Gandhi had fallen, but his ideals stood tall.

Today, Mahatma Gandhi’s legacy lives on—in India’s Constitution, in global movements for civil rights, and in the hearts of those who believe in peace. His teachings influenced leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and Dalai Lama. His birthday, Gandhi Jayanti, is celebrated as the International Day of Non-Violence.

Mahatma Gandhi was more than a man—he was a movement. His life was a message. His death was a sacrifice. And his legacy is a challenge to every generation: to choose truth over fear, peace over violence, and love over hatred.

“You may never know what results come of your actions. But if you do nothing, there will be no result.” – Mahatma Gandhi

Table of Contents

🗣️ Mahatma Gandhi’s Quit India Speech – A Legacy of Courage and Nonviolence

Date: August 8, 1942

Time: 9:00 PM to midnight

Location: Gowalia Tank Maidan, Bombay (now August Kranti Maidan)

Audience: Thousands of Congress delegates, freedom fighters, and citizens

🔹 Opening Invocation: A Nation on the Brink

It was the night of August 8, 1942, and the air in Bombay was electric with anticipation. At Gowalia Tank Maidan, thousands had gathered—Congress leaders, students, women, workers, and ordinary citizens. The All India Congress Committee was in session, but the real power pulsed in the crowd. As the clock neared midnight, I, Mahatma Gandhi, stood before my people—not in a palace, but in a public ground, ready to ignite a revolution of the soul.

“Before you discuss the resolution, let me place before you one or two things. I want you to understand them clearly and consider them from the same point of view from which I am placing them before you.”

🔹 The Moral Foundation of the Movement

I am the same Mahatma Gandhi you knew in 1920. My faith in nonviolence, in truth, and in the soul of India has only grown stronger. Today, I stand before you not as a politician, but as a servant of the people, as a soldier of peace, and as a seeker of justice.

The Quit India Movement is not born out of hatred—it is born out of Ahimsa, the purest form of nonviolence. If there is anyone among you who has lost faith in Ahimsa, let him not vote for this resolution. But if you believe in the power of truth and love, then stand with me.

Mahatma Gandhi does not seek power. I seek freedom—not for myself, but for every Indian, every farmer, every woman, every child. This is not a drive for dominance. It is a nonviolent fight for India’s independence, rooted in the belief that no empire can hold captive the soul of a nation.

🔹 The Global Context: A World in Flames

The world is burning. Nations are at war. Russia and China are threatened. Europe is in ruins. The earth is scorched by the flames of violence. In this crisis, if I fail to use the weapon of Ahimsa that God has given me, I shall be judged unworthy of that gift.

Mahatma Gandhi cannot remain silent when injustice reigns. I must act now. I may not hesitate. I may not merely look on. I must speak, and I must lead.

🔹 The Nature of Our Struggle

This is not a violent revolution. This is a nonviolent revolution of the spirit. In violent struggles, generals often seize power and become dictators. But under the Congress scheme of things, which is essentially nonviolent, there can be no room for dictatorship.

A nonviolent soldier of freedom covets nothing for himself. He fights only for the freedom of his country. The Congress is unconcerned as to who will rule when freedom is attained. The power, when it comes, will belong to the people of India. It will be for them to decide to whom it is entrusted.

🔹 The Call to Action – Do or Die

“Here is a mantra, a short one, that I give you. You may imprint it on your hearts and let every breath of yours give expression to it. The mantra is: ‘Do or Die.’ We shall either free India or die in the attempt; we shall not live to see the perpetuation of our slavery.”

This is not a slogan. It is a vow. It is a sacred pledge. Mahatma Gandhi does not ask you to kill. I ask you to resist. I ask you to suffer. I ask you to sacrifice. But above all, I ask you to remain nonviolent, even in the face of brutality.

🔹 The Role of Youth and Women

To the youth of India, I say—this is your moment. Rise with courage. Rise with discipline. Let your hearts be pure and your actions noble. Do not be swayed by anger. Let your resistance be rooted in love.

To the women of India, I say—you are the soul of this nation. Your strength, your sacrifice, your silence, and your suffering have built this land. Now, let your voice be heard. Join the movement. Lead the movement. Let Mahatma Gandhi’s dream of an inclusive, just India be fulfilled through your grace.

🔹 The Power of Nonviolence

Nonviolence is not weakness. It is strength. It is the strength of the soul. It is the strength that comes from truth. Mahatma Gandhi has seen its power in South Africa, in Champaran, in Kheda, and in Dandi. Now, let the world see its power in the streets of India.

Let no one commit a wrong in anger. Let there be no breach of peace. Let our resistance be disciplined, organized, and spiritual. Let every village become a fortress of nonviolence. Let every home become a temple of truth.

🔹 The Role of Congress and the People

Once I am arrested, the responsibility shifts to the Congress Working Committee. But the real power lies with you—the people. You are the guardians of this movement. You are the torchbearers of freedom.

Mahatma Gandhi asks you to remain united. Let there be no division of caste, creed, or religion. Let Hindus and Muslims, Sikhs and Christians, Parsis and Jains stand together. Let India rise as one.

🔹 The Vision of Free India

What do we seek? We seek Swaraj—self-rule. We seek dignity. We seek justice. We seek a nation where the poorest have a voice, where women walk free, where children are educated, and where truth reigns.

Mahatma Gandhi does not dream of palaces. I dream of villages with spinning wheels, with clean water, with schools, and with peace. I dream of an India that is free not just from British rule, but from poverty, ignorance, and fear.

🔹 Closing Benediction

“I believe that in the storm that is raging around us, if we remain true to our pledge of nonviolence, we shall emerge stronger, purer, and freer.”

Let this be our prayer. Let this be our pledge. Let this be our legacy.

I am Mahatma Gandhi. I am your servant. I am your voice. I am your hope. Let us walk together—through fire, through pain, through sacrifice—until India is free.

🔹 Part 1: Origins of Mahatma Gandhi – Roots of a Revolutionary

🧬 Section 1: Birth and Lineage of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in Porbandar, a coastal town in present-day Gujarat, India. His birth name was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, but the world would come to know him as Mahatma Gandhi—a title meaning “great soul,” first bestowed upon him in South Africa in 1914.

Porbandar, a princely state under British suzerainty, was a place of modest prosperity and deep cultural traditions. Mahatma Gandhi’s family belonged to the Bania caste, traditionally associated with commerce, but his lineage was steeped in administrative service. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as the Diwan (chief minister) of Porbandar and later of Rajkot. Known for his integrity and practical wisdom, Karamchand Gandhi was a respected figure in local governance.

Mahatma Gandhi’s mother, Putlibai Gandhi, was a devout practitioner of Vaishnavism, deeply influenced by Jain traditions. Her daily rituals, fasting, and spiritual discipline left a lasting impression on young Mahatma Gandhi. She taught him the values of truth (satya), nonviolence (ahimsa), and self-restraint, which would later become the pillars of Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy.

🧠 Section 2: Childhood Traits and Early Personality

As a child, Mahatma Gandhi was quiet, introspective, and unusually sensitive. He was nicknamed “Moniya” by his family—a name that reflected his gentle nature. Unlike other children, Mahatma Gandhi preferred solitude and contemplation. He was not particularly athletic or outspoken, but he was deeply curious and observant.

Mahatma Gandhi’s early education began in Porbandar and continued in Rajkot. He was an average student, shy and hesitant to speak in public. Yet, he showed a strong moral compass even in childhood. One of the most telling incidents involved Mahatma Gandhi stealing a bit of gold from his brother’s armlet. Overcome with guilt, he confessed in writing to his father, who responded with silent forgiveness. This moment etched in Mahatma Gandhi’s mind the power of truth and the nobility of nonviolence.

His exposure to religious texts like the Ramayana, Bhagavad Gita, and stories of Shravana and Harishchandra further shaped his ethical foundation. Mahatma Gandhi was fascinated by tales of sacrifice, duty, and righteousness. These stories didn’t just entertain him—they molded his worldview.

💍 Section 3: Marriage to Kasturba Gandhi

At the age of 13, Mahatma Gandhi was married to Kasturba Makhanji, a girl of similar age, in a traditional arranged ceremony. This early marriage was customary in 19th-century India, but it introduced Mahatma Gandhi to the complexities of companionship, responsibility, and emotional growth.

Initially, Mahatma Gandhi struggled with possessiveness and immaturity in the relationship. He later admitted to feelings of jealousy and control, which he deeply regretted. Over time, Kasturba Gandhi became not just his wife but his partner in activism, enduring prison, fasting, and public service alongside him.

Their marriage produced four sons—Harilal, Manilal, Ramdas, and Devdas. While Mahatma Gandhi’s relationship with his children, especially Harilal, was strained due to ideological differences, his bond with Kasturba remained resilient. She was his emotional anchor, and her quiet strength complemented his public resolve.

🕉️ Section 4: Religious and Philosophical Influences

Mahatma Gandhi’s upbringing was a confluence of Hinduism, Jainism, and Vaishnavism. His mother’s devotion to rituals and fasting introduced him to the concept of self-purification. Jain principles of nonviolence, vegetarianism, and truthfulness became central to Mahatma Gandhi’s moral framework.

He was also influenced by Bhakti traditions, which emphasized personal devotion and humility. Mahatma Gandhi’s spiritual journey was not dogmatic—it was experiential. He questioned, experimented, and internalized beliefs through practice.

Later in life, Mahatma Gandhi would describe religion as a personal quest for truth, not a rigid set of doctrines. His early exposure to diverse spiritual paths allowed him to embrace interfaith harmony, a theme that would define his leadership during India’s communal tensions.

⚖️ Section 5: First Encounters with Injustice and Introspection

Even before his famous train incident in South Africa, Mahatma Gandhi experienced subtle forms of injustice. As a child, he witnessed caste discrimination, gender inequality, and colonial arrogance. These experiences planted seeds of resistance in his mind.

One formative moment was his realization of British superiority complex in education and governance. Mahatma Gandhi began to question why Indians were treated as second-class citizens in their own land. His introspection deepened during adolescence, leading him to explore ethical living, self-discipline, and truth-seeking.

Mahatma Gandhi’s decision to become a barrister was not just a career move—it was a step toward understanding law, justice, and reform. His journey to England in 1888 would further expand his worldview, but the roots of his revolutionary spirit were already growing in Porbandar and Rajkot.

🧩 Section 6: Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi’s Early Years

The early life of Mahatma Gandhi was not marked by dramatic events or heroic feats. It was shaped by quiet observations, moral dilemmas, and spiritual depth. These formative years laid the foundation for a man who would later challenge empires, inspire continents, and redefine resistance.

His childhood taught him that truth is strength, that nonviolence is power, and that simplicity is revolutionary. Mahatma Gandhi’s roots were not in politics—they were in family, faith, and introspection.

“In a gentle way, you can shake the world.” – Mahatma Gandhi

This quote reflects the essence of his early life—a gentle soul preparing to shake the foundations of colonialism.

🔹 Part 2: Mahatma Gandhi in England – The Making of a Barrister

🛳️ Departure from India: A Young Man’s Leap into the Unknown

In September 1888, an 18-year-old Mahatma Gandhi boarded the SS Clyde from Bombay, bound for London. His goal: to study law and become a barrister at the prestigious Inner Temple. This decision was bold and controversial. Crossing the seas was considered taboo by his caste elders, and many feared he would lose his religion and cultural identity. But Mahatma Gandhi, driven by ambition and curiosity, was undeterred.

Before leaving, Mahatma Gandhi made three sacred promises to his mother, Putlibai Gandhi, under the guidance of a Jain monk named Becharji Swami:

- He would abstain from meat

- He would avoid alcohol

- He would remain celibate

These vows were not just personal—they became the moral compass of Mahatma Gandhi’s life. They reflected his commitment to truth, self-discipline, and spiritual purity, values that would later define his leadership.

🇬🇧 Arrival in London: Culture Shock and Identity Crisis

Mahatma Gandhi arrived in London in late October 1888. The city was vast, cold, and unfamiliar. He was overwhelmed by its pace, fashion, and customs. Determined to fit in, Mahatma Gandhi initially tried to adopt British manners. He bought a top hat, a tailcoat, and even took elocution lessons to improve his English accent. He enrolled in ballroom dancing classes and attempted to learn the violin—all in an effort to become a “gentleman.”

But this phase was short-lived. Mahatma Gandhi soon realized that imitation brought him no peace. He felt alienated, both culturally and spiritually. The more he tried to become British, the more he lost touch with his roots. This identity crisis led him to introspection and a deeper search for meaning.

🥗 Vegetarianism and the London Vegetarian Society

One of the first challenges Mahatma Gandhi faced was food. As a strict vegetarian, he struggled to find suitable meals in London. Initially, he survived on sweets and fruits. But soon, he discovered the London Vegetarian Society, a community that embraced ethical eating and spiritual living.

Joining the society was a turning point. Mahatma Gandhi began reading books on vegetarianism, nutrition, and ethics. He met influential thinkers like Dr. Josiah Oldfield, who introduced him to the idea that food choices were linked to moral and spiritual health. Gandhi even contributed articles to the society’s journal, The Vegetarian, and attended regular meetings.

This experience deepened Mahatma Gandhi’s commitment to nonviolence, not just in action but in consumption. He began to see vegetarianism as a form of Ahimsa, a principle that would later become central to his political philosophy.

📖 Theosophy and the Bhagavad Gita: Spiritual Awakening

During his time in London, Mahatma Gandhi encountered members of the Theosophical Society, including Annie Besant and Helena Blavatsky. Theosophy promoted universal brotherhood, spiritual inquiry, and the study of ancient texts. Gandhi was intrigued by their openness and their reverence for Indian scriptures.

It was through the Theosophists that Mahatma Gandhi first read the Bhagavad Gita, in an English translation by Sir Edwin Arnold titled The Song Celestial. Though raised in a religious household, Gandhi had never studied the Gita deeply. In London, it became his spiritual guide.

The Gita’s teachings on duty (dharma), detachment, and selfless action resonated deeply. Mahatma Gandhi later wrote, “When doubts haunt me, when disappointments stare me in the face… I turn to the Bhagavad Gita and find a verse to comfort me.”

This spiritual awakening marked a shift. Mahatma Gandhi began to see life as a moral journey, where truth and service were more important than success or status.

⚖️ Legal Studies at the Inner Temple

Mahatma Gandhi enrolled at the Inner Temple on November 6, 1888, one of the four Inns of Court in London. The Inner Temple was a bastion of legal tradition, and Gandhi studied subjects like Roman law, jurisprudence, and legal procedure.

He was a diligent student, though not particularly distinguished. He avoided social gatherings and focused on his studies. In June 1891, Mahatma Gandhi was called to the Bar, officially becoming a barrister.

Despite earning his qualification, Gandhi later admitted that he learned little about the practical aspects of law. His real education, he said, came from life outside the classroom—from books, debates, and personal reflection.

🧠 Intellectual Influences: Ruskin, Tolstoy, and Thoreau

While in London, Mahatma Gandhi read widely. Three thinkers had a profound impact on him:

- John Ruskin: His book Unto This Last taught Gandhi that the dignity of labor and the welfare of the poor were central to a just society.

- Leo Tolstoy: His writings on Christianity, nonviolence, and moral living inspired Gandhi’s later correspondence and activism.

- Henry David Thoreau: His essay Civil Disobedience introduced Gandhi to the idea of resisting unjust laws through peaceful means.

These intellectual influences helped Mahatma Gandhi shape his philosophy of Satyagraha—truth-force or soul-force—a method of nonviolent resistance that would later challenge the British Empire.

🇮🇳 Return to India: A Barrister Without a Voice

Mahatma Gandhi returned to India in June 1891, shortly after his call to the Bar. He was 22 years old. Tragically, his mother had passed away while he was abroad—a loss that deeply affected him.

Back in Rajkot, Gandhi attempted to establish a law practice. But he struggled with courtroom procedure and public speaking. His first case ended in embarrassment when he couldn’t cross-examine a witness. Clients were hesitant to trust a young, inexperienced barrister who lacked confidence.

This period of failure was humbling. Mahatma Gandhi felt lost and directionless. But it also prepared him for his next chapter. In 1893, he accepted a one-year contract to work for an Indian firm in South Africa—a move that would awaken his political consciousness and set him on the path to becoming the Mahatma.

🧭 Legacy of the London Years

The years 1888 to 1891 were transformative for Mahatma Gandhi. In London, he confronted cultural alienation, personal doubt, and moral dilemmas. But he also discovered the power of self-discipline, spiritual inquiry, and ethical living.

His exposure to vegetarianism, Theosophy, and the Bhagavad Gita laid the foundation for his later philosophy of Satyagraha. Though his legal career in India faltered, the seeds of greatness had been sown. The young man who left India as Mohandas Gandhi would soon return to the world stage as Mahatma Gandhi, the architect of India’s nonviolent revolution.

🔍 Sources and Historical Proof

- The Story of My Experiments with Truth – Autobiography by Mahatma Gandhi

- Inner Temple Archives

- Mahatma Gandhi and the Bhagavad Gita – mkgandhi.org

- Gandhi Before India by Ramachandra Guha

- Gandhi: The Years That Changed the World by Ramachandra Guha

- London Vegetarian Society Archives

🔹 Part 3: Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa – Birth of Satyagraha and the Rise of a Revolutionary

🛬 Arrival in Durban: A Contract and a Turning Point

In May 1893, a 24-year-old Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Durban, South Africa, to serve as legal counsel for Dada Abdulla & Co., a prominent Indian merchant firm. Gandhi had accepted a one-year contract to assist in a commercial dispute in the Transvaal. He expected a routine legal assignment—but South Africa would become the crucible in which his philosophy and leadership were forged.

🚉 The Train Incident: A Defining Moment

Just days after his arrival, Mahatma Gandhi boarded a train to Pretoria. Despite holding a valid first-class ticket, he was ordered to move to a third-class compartment because of his race. When he refused, he was forcibly thrown off the train at Pietermaritzburg station, left shivering in the cold.

This incident was a turning point. Gandhi later wrote in his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, that this humiliation awakened his resolve to fight injustice—not with violence, but with moral courage.

“It was a symptom of the deep disease of colour prejudice. I decided to fight, not with fists, but with soul.”

⚖️ Legal Work and Activism for Indian Rights

Mahatma Gandhi completed his legal duties for Dada Abdulla, but the plight of Indians in South Africa—especially indentured laborers and traders—moved him deeply. They faced:

- Pass laws requiring special permits for movement

- Denial of voting rights

- Restrictions on land ownership

- Licensing discrimination for Indian businesses

Instead of returning to India, Gandhi chose to stay and fight. He began organizing meetings, writing petitions, and educating the community about their rights. His legal background gave him credibility, but it was his moral clarity and humility that won hearts.

🏛️ Formation of the Natal Indian Congress (NIC)

In 1894, Mahatma Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) in Durban. The NIC became the first organized political body representing Indian interests in South Africa. Its goals were:

- To fight racial discrimination through legal means

- To unite Indians across religious and linguistic lines

- To challenge unjust colonial laws through peaceful protest

The NIC mobilized mass petitions, including one with 10,000 signatures opposing a bill to disenfranchise Indians. Gandhi’s leadership was inclusive—he brought together Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, and Christians under a shared vision of dignity and justice.

📰 Indian Opinion: A Voice for the Voiceless

In 1903, Mahatma Gandhi launched Indian Opinion, a weekly newspaper printed in English, Gujarati, Hindi, and Tamil. It became a powerful tool for communication, education, and mobilization.

Through Indian Opinion, Gandhi:

- Reported injustices faced by Indians

- Explained the principles of nonviolence

- Encouraged unity and self-respect

- Criticized colonial policies with reasoned arguments

The newspaper was printed at the Phoenix Settlement, a self-sufficient community Gandhi established near Durban. It embodied his ideals of simple living, manual labor, and collective responsibility.

🧘 Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm: Living the Change

Inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s book The Kingdom of God Is Within You, Mahatma Gandhi created two experimental communities:

- Phoenix Settlement (1904) near Durban

- Tolstoy Farm (1910) near Johannesburg

These were not just homes—they were laboratories for ethical living. Residents practiced:

- Vegetarianism

- Manual labor

- Education without punishment

- Interfaith harmony

- Self-reliance

Mahatma Gandhi believed that political change must be rooted in personal transformation. These settlements were his way of living the change he preached.

🔥 First Use of Nonviolent Resistance: Birth of Satyagraha

In 1906, the Transvaal government passed the Asiatic Registration Act, requiring all Indians to carry registration certificates and submit to fingerprinting. It was dehumanizing and discriminatory.

Mahatma Gandhi responded not with riots, but with Satyagraha—a new philosophy of resistance. The word, coined by Gandhi, means “truth-force” or “soul-force.” It combined:

- Ahimsa (nonviolence)

- Satya (truth)

- Tapasya (self-suffering)

On September 11, 1906, at a mass meeting in Johannesburg, thousands of Indians took a pledge to defy the law peacefully. This was the first organized Satyagraha campaign.

Over the next seven years, Mahatma Gandhi led multiple Satyagraha movements:

- Burning of registration certificates

- Peaceful marches and protests

- Voluntary arrests

- Refusal to pay unjust taxes

More than 2,000 Indians were jailed. Gandhi himself was arrested multiple times, beaten, and humiliated. But he never retaliated. His courage inspired global admiration.

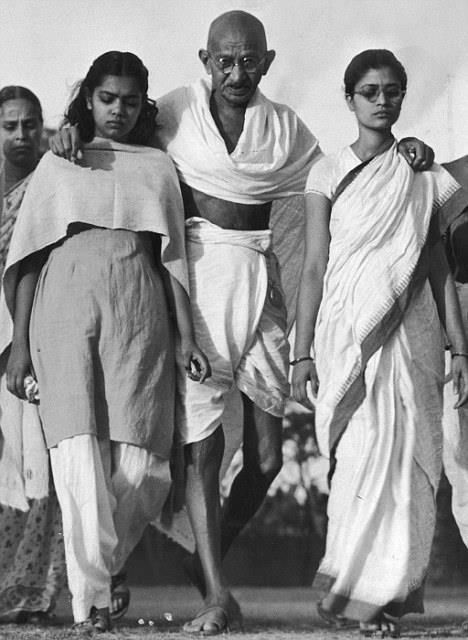

👩🌾 The 1913 Women’s March: Expanding the Movement

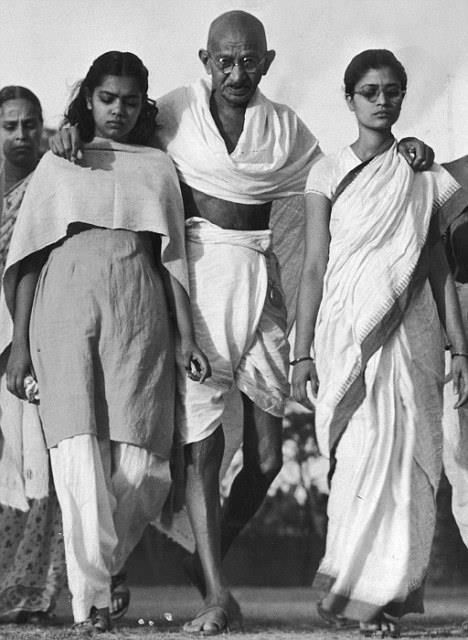

In 1913, Mahatma Gandhi expanded Satyagraha to include Indian women, who were often overlooked in political activism. The government had imposed a £3 tax on indentured laborers and banned inter-provincial travel without permits.

Gandhi organized a march of women from Natal to Transvaal, led by figures like Kasturba Gandhi and Narayani. Hundreds were arrested, but the movement gained momentum.

This marked a shift in Mahatma Gandhi’s strategy—he now saw women as equal partners in resistance. Their courage and sacrifice became central to the freedom struggle.

🧑⚖️ Negotiations and Victory

After years of protest, arrests, and international pressure, the South African government began negotiations. In 1914, Mahatma Gandhi reached an agreement with General Jan Smuts, resulting in:

- Repeal of the Asiatic Registration Act

- Recognition of Indian marriages

- Abolition of the £3 tax

It was a moral victory. Mahatma Gandhi had proven that nonviolence could defeat injustice. His reputation soared—not just in South Africa, but across the British Empire.

✈️ Departure from South Africa: A New Mission Awaits

In July 1914, Mahatma Gandhi left South Africa for England, and then returned to India in January 1915. He was 45 years old. He had spent 21 years in South Africa, transforming from a shy lawyer into a global symbol of resistance.

Before leaving, he was honored with the title “Mahatma”, meaning “great soul,” by South African Indians. It was a recognition of his spiritual leadership and moral courage.

🧭 Legacy of the South African Years

Mahatma Gandhi’s time in South Africa was not a detour—it was a crucible. It shaped his:

- Philosophy of Satyagraha

- Commitment to nonviolence

- Belief in community living

- Respect for all religions

- Empowerment of women and the poor

These principles would guide his leadership in India’s freedom movement. South Africa was where Mahatma Gandhi was born—not biologically, but spiritually and politically.

Sources:

- Natal Indian Congress & Gandhiji’s Early Career and Activism

- 131 years of Pietermaritzburg incident

- Gandhi’s First Satyagraha in South Africa

🔹 Part 4: Mahatma Gandhi Returns to India – Awakening the Nation (1915–1919)

🛬 Return in 1915: A Hero’s Welcome and a Humble Start

After two transformative decades in South Africa, Mahatma Gandhi returned to India in January 1915. He was 46 years old, already known for his successful campaigns against racial injustice and for pioneering Satyagraha. At Mumbai’s Apollo Bunder, crowds gathered to welcome him, but Gandhi did not plunge into politics immediately.

Instead, he followed the advice of his mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who urged him to “first understand India before you try to lead it.” Gokhale recognized Gandhi’s moral authority and spiritual depth, calling him a “hero and martyr-maker.” But he also knew that Gandhi’s South African experience needed grounding in Indian realities.

🚶 Tours Across India: Listening Before Leading

For the next year, Mahatma Gandhi traveled extensively across India. He visited:

- Shantiniketan, the school of Rabindranath Tagore

- The Kumbh Mela at Haridwar

- Villages in Bihar, Gujarat, and Maharashtra

He observed poverty, caste oppression, and colonial exploitation firsthand. Gandhi refrained from political speeches and focused on reconnecting with India’s soul—its villages, farmers, and workers. This period shaped his belief that India’s salvation lay not with the elite, but with the masses.

🏡 Founding of Sabarmati Ashram: A Laboratory for Truth

In May 1915, Mahatma Gandhi established the Satyagraha Ashram at Kochrab, near Ahmedabad. In 1917, it was relocated to the banks of the Sabarmati River, becoming the iconic Sabarmati Ashram.

The Ashram was more than a residence—it was a training ground for Gandhi’s followers. It emphasized:

- Simplicity and self-reliance

- Manual labor and spinning

- Community service

- Moral discipline

Ashramites became Gandhi’s core team in future movements. The Ashram embodied his vision of spiritual nationalism, where personal ethics and public service were inseparable.

🎤 First Public Appearance: Banaras Hindu University (1916)

In February 1916, Mahatma Gandhi made his first major public speech at the Banaras Hindu University during its inauguration. He shocked the elite audience by criticizing the disconnect between Indian nationalism and the poor.

“Is it right that while we are talking of Swaraj, we should have palatial buildings and luxurious living, while the masses starve?”

This speech revealed Gandhi’s vision: a nationalism rooted in the struggles of farmers and laborers, not lawyers and landlords.

🌾 Champaran Satyagraha (1917): Justice for Indigo Farmers

Mahatma Gandhi’s first major political intervention came in Champaran, Bihar, where British planters forced peasants into the exploitative Tinkathia system—growing indigo on fixed portions of land at unfair prices.

Gandhi arrived in Champaran in April 1917, conducted surveys, and defied British orders to leave. His civil disobedience led to a formal inquiry and eventual abolition of the system.

Champaran was a turning point. It showed that nonviolent resistance could win rural justice. Gandhi’s method of truth-seeking, mass mobilization, and peaceful defiance became a blueprint for future movements.

🧑🏭 Ahmedabad Mill Strike (1918): Workers’ Rights and Moral Leadership

In 1918, Mahatma Gandhi mediated a dispute between mill workers and owners in Ahmedabad. Workers demanded better wages; owners resisted. Gandhi advised workers to strike peacefully and even undertook a fast unto death to uphold their cause.

His moral pressure led to a compromise. This was Gandhi’s first major involvement with urban labor, and it reinforced his belief that truth and sacrifice could resolve class conflict.

🌾 Kheda Satyagraha (1918): Relief for Peasants

Also in 1918, famine struck Kheda district in Gujarat. Peasants were unable to pay land taxes, but the British refused exemptions. Gandhi led a Satyagraha, urging peasants to withhold payment.

The movement was disciplined and nonviolent. Eventually, the government relented, granting tax relief. Kheda proved that local struggles could challenge imperial policies, and that Gandhi’s leadership could unite diverse communities.

🏛️ Rise in Indian National Congress: From Outsider to Leader

Until 1919, Mahatma Gandhi remained on the fringes of national politics. He avoided joining the Home Rule Movement, believing it was too elitist and premature. But his success in Champaran, Kheda, and Ahmedabad earned him respect across India.

By 1919, Gandhi had become a central figure in the Indian National Congress. His emphasis on mass mobilization, nonviolence, and inclusive nationalism reshaped the party’s direction.

He brought new energy to the Congress:

- Engaging peasants and workers

- Promoting Khadi and Swadeshi

- Opposing untouchability

- Uniting Hindus and Muslims

🌍 Additional Topics: Kaisar-i-Hind Medal and Political Philosophy

In June 1915, Mahatma Gandhi was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Gold Medal by Lord Hardinge for his humanitarian work in South Africa. Though later returned in protest, it showed that Gandhi was initially seen as a reformer, not a rebel.

His early political philosophy emphasized:

- Moral authority over political power

- Decentralized village governance

- Education through character building

- Swaraj as self-rule, not just independence

🧭 Legacy of the Early Indian Years

Between 1915 and 1919, Mahatma Gandhi:

- Reconnected with India’s grassroots

- Proved the power of Satyagraha in Indian soil

- United diverse communities through ethical leadership

- Transformed the Congress from elite to mass-based

This phase laid the foundation for future movements like Non-Cooperation, Civil Disobedience, and Quit India. Gandhi had emerged not just as a political leader, but as the moral compass of India’s freedom struggle.

Sources:

- Rise of Gandhi: Champaran, Kheda and Ahmedabad Mill Strike

- Arrival of Mahatma Gandhi in India (1915)

- Gandhi’s Early Movements in India

🔹 Part 5: Mahatma Gandhi’s Movements – Salt, Swadeshi, and Swaraj (1920–1942)

🧭 Introduction: From Protest to Nation-Building

Between 1920 and 1942, Mahatma Gandhi led India through its most transformative phase of the freedom struggle. These years saw the rise of mass movements—Non-Cooperation, Civil Disobedience, and Quit India—alongside a parallel revolution in thought, lifestyle, and social reform. Gandhi’s vision of Swaraj was not just political independence; it was a complete reimagining of Indian society rooted in truth, nonviolence, self-reliance, and moral courage.

✊ Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–1922): The Awakening of the Masses

The Non-Cooperation Movement, launched by Mahatma Gandhi in August 1920, was a response to:

- The Rowlatt Act (1919), which allowed detention without trial

- The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, where British troops killed hundreds of peaceful protesters

- The Khilafat issue, which galvanized Muslim support

Gandhi urged Indians to:

- Boycott British schools, courts, and titles

- Resign from government jobs

- Refuse to buy foreign cloth

- Return British honors (including his own Kaisar-i-Hind medal)

This was the first time Mahatma Gandhi mobilized millions across caste, class, and religion. The movement was peaceful, disciplined, and deeply spiritual. Gandhi emphasized that nonviolence (Ahimsa) was not passive—it was active resistance through moral force.

However, after the Chauri Chaura incident in February 1922—where protesters killed 22 policemen—Gandhi suspended the movement. He declared, “Violence has no place in Satyagraha.” This decision disappointed many but reaffirmed Gandhi’s unwavering commitment to nonviolence.

🧵 Charkha and Khadi: Symbols of Swadeshi and Self-Reliance

To Mahatma Gandhi, economic independence was inseparable from political freedom. He revived the Charkha (spinning wheel) and promoted Khadi (handspun cloth) as symbols of resistance.

Khadi was not just cloth—it was a moral statement:

- Rejecting British industrial goods

- Empowering rural artisans

- Promoting dignity of labor

Gandhi said, “Khadi is the sun of the village solar system.” He made spinning a daily ritual and urged every Indian to wear Khadi. The Swadeshi movement, rooted in local production and consumption, became a cornerstone of Gandhi’s constructive program.

Khadi also became a tool for social unity. In Gandhi’s ashrams, Hindus, Muslims, and Dalits spun together, breaking caste barriers. The Charkha became a symbol of peace, self-help, and national pride.

🧂 Dandi March and Salt Satyagraha (1930): Defying Empire with a Handful of Salt

In January 1930, the British ignored Gandhi’s 11 demands, which included:

- Abolition of the salt tax

- Reduction of land revenue

- Release of political prisoners

On March 12, 1930, Mahatma Gandhi began the Dandi March, walking 240 miles from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi with 78 volunteers. On April 6, he picked up a handful of salt from the shore, breaking the law.

This act sparked a nationwide Salt Satyagraha:

- Mass production of illegal salt

- Boycotts of British goods

- Peaceful protests and arrests

Over 60,000 people were jailed, including Gandhi. The movement drew global attention. American journalist Webb Miller’s reports on the Dharasana Salt Works protest, where satyagrahis were brutally beaten, shocked the world.

The Salt Satyagraha culminated in the Gandhi-Irwin Pact (1931):

- Political prisoners were released

- Gandhi agreed to attend the Second Round Table Conference in London

Though the conference failed, the Salt March proved that simple acts of defiance could shake empires.

📜 Civil Disobedience Movement (1930–1934): Lawbreaking as Protest

The Civil Disobedience Movement extended the Salt Satyagraha into a broader campaign. Indians:

- Refused to pay taxes

- Boycotted British institutions

- Defied unjust laws

Mahatma Gandhi was arrested repeatedly. The movement spread to:

- Tamil Nadu, led by C. Rajagopalachari

- Malabar, led by K. Kelappan

- North-West Frontier Province, led by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan

Women played a key role. Leaders like Kasturba Gandhi, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, and Hansaben Mehta led protests, picketed shops, and courted arrest.

Despite brutal repression, the movement persisted. It showed that civil disobedience was a powerful tool for mass mobilization, rooted in discipline and sacrifice.

🔥 Quit India Movement (1942): Do or Die

In August 1942, amid World War II, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement at Gowalia Tank Maidan, Bombay. His call: “Do or Die.”

The movement was triggered by:

- The failure of the Cripps Mission

- Britain’s refusal to grant independence

- Rising nationalist impatience

Within hours, Gandhi and Congress leaders were arrested. The movement became leaderless but unstoppable:

- Students led underground networks

- Usha Mehta ran a secret radio station

- Parallel governments emerged in Ballia, Tamluk, and Satara

The British responded with:

- Mass arrests (over 100,000)

- Censorship and martial law

- Violent crackdowns (over 1,000 killed)

Though suppressed, Quit India marked the final mass uprising before independence. It showed that India was ungovernable without Indian consent.

🧱 Constructive Programs: Building Swaraj from the Ground Up

Beyond protests, Mahatma Gandhi emphasized constructive work—grassroots efforts to rebuild India’s social fabric. His programs included:

- Village sanitation

- Basic education (Nai Talim)

- Promotion of Khadi

- Upliftment of women

- Eradication of untouchability

- Communal harmony

- Economic equality

Gandhi believed that true Swaraj meant self-rule in every village. He wrote, “Constructive Programme is the truthful and nonviolent way of winning Poorna Swaraj”.

These efforts were not side projects—they were the foundation of Gandhi’s revolution. He said, “My real politics is constructive work.”

🕊️ Hindu-Muslim Unity and Fight Against Untouchability

Mahatma Gandhi worked tirelessly to bridge communal divides. He supported the Khilafat Movement to align Hindu-Muslim interests. He condemned riots and fasted to restore peace in Noakhali and Calcutta.

He called untouchability a “sin against God and man.” He renamed Dalits as Harijans (children of God) and launched campaigns for:

- Temple entry

- Inter-caste dining

- Dalit education

Gandhi’s efforts were spiritual and political. He believed that freedom was meaningless without social justice.

🧭 Conclusion: A Revolution of the Soul

Between 1920 and 1942, Mahatma Gandhi led India through a revolution unlike any other. His movements were not just political—they were spiritual awakenings, rooted in truth, sacrifice, and love.

He mobilized millions, challenged empires, and redefined resistance. But more than that, he built a new India from the ground up—one spinning Khadi, rejecting caste, and dreaming of Swaraj.

Gandhi’s legacy is not just in the freedom he helped win, but in the values he left behind. His movements remain a blueprint for ethical leadership, grassroots change, and the power of nonviolence.

Sources: Gandhi Quotes on Khadi and Swadeshi – Mani Bhavan

Civil Disobedience Movement – Prepp

Constructive Programme – MK Gandhi

Quit India Movement – Wikipedia

🔹 Part 6: Mahatma Gandhi’s Personal Life – Simplicity and Struggles

Mahatma Gandhi’s public life is well documented, but his personal life—marked by simplicity, spiritual discipline, and emotional complexity—is equally profound. From his marriage to Kasturba and strained relationship with his sons to his controversial celibacy experiments and austere lifestyle in Sabarmati and Sevagram, Gandhi’s private world reveals the human behind the Mahatma. This chapter explores the inner struggles, ethical experiments, and criticisms that shaped his legacy.

💍 Kasturba Gandhi: Partner in Life and Struggle

Kasturba Gandhi, born in 1869, married Mohandas Gandhi at the age of 13. Their early relationship was traditional, with Gandhi often exercising control over her choices. However, Kasturba evolved into a strong, independent figure who supported Gandhi through every phase of his public life.

She:

- Endured multiple imprisonments alongside Gandhi

- Participated in protests, including the Salt Satyagraha

- Managed household and Ashram affairs during Gandhi’s absences

In 1944, Kasturba died in prison at Aga Khan Palace, Pune, after months of illness. Gandhi was devastated. Her death marked the end of a 62-year companionship. He wrote, “She helped me to become what I am.”

👨👦 Relationship with Sons, Especially Harilal

Mahatma Gandhi had four sons: Harilal, Manilal, Ramdas, and Devdas. His relationship with Harilal Gandhi, the eldest, was particularly strained.

Harilal:

- Resented Gandhi’s refusal to support his ambition to become a barrister

- Converted to Islam briefly, then reconverted to Hinduism

- Struggled with alcoholism and poverty

Gandhi’s letters to Harilal reveal disappointment and sorrow. He once wrote, “You are my son, but you are no longer my pride.” Their estrangement highlighted Gandhi’s rigid expectations and emotional distance.

Despite reconciliation attempts, Harilal died in obscurity in 1948, just months after Gandhi’s assassination.

🧪 Experiments with Truth and Celibacy

Gandhi’s autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, outlines his lifelong quest for moral purity. One of the most controversial aspects was his celibacy (brahmacharya), which he adopted in 1906 at age 38.

He believed:

- Celibacy enhanced spiritual strength

- Sexual desire distracted from service and truth

- Control over senses was essential for self-realization

His methods were extreme:

- He slept beside young women, including his grandniece Manu Gandhi, to test his restraint

- He discouraged sexual relations even within marriage

- He advised cold baths and mental diversion to suppress desire

Critics, including Jawaharlal Nehru, called these practices “abnormal and unnatural.” Gandhi’s celibacy experiments remain one of the most debated aspects of his life.

🏡 Ashram Life: Sabarmati and Sevagram

🕊️ Sabarmati Ashram (1917–1930)

Located on the banks of the Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad, this Ashram was Gandhi’s base during major movements like:

- Non-Cooperation

- Salt Satyagraha

It emphasized:

- Khadi production

- Manual labor

- Interfaith prayer

- Education and sanitation

Gandhi lived in Hridaya Kunj, a modest cottage. The Ashram was a living laboratory of his ideals: simplicity, discipline, and community service.

🌾 Sevagram Ashram (1936–1948)

After vowing not to return to Sabarmati until India gained independence, Gandhi moved to Sevagram, a village near Wardha.

Here, he:

- Lived in a hut called Bapu Kuti

- Held prayer meetings and political discussions

- Promoted village upliftment and self-sufficiency

Sevagram had no electricity or postal services initially. Gandhi renamed the village “Sevagram”—the village of service.

🕰️ Daily Routine, Diet, and Fasts

Gandhi’s daily life was austere and disciplined:

- Woke at 4 AM for prayer and spinning

- Ate simple meals: boiled vegetables, fruit, goat’s milk

- Walked barefoot, even in cold weather

- Slept on a mat with minimal possessions

He believed in dietary self-control:

- Avoided spices, sweets, and processed foods

- Practiced fruitarianism and raw diets

- Wrote extensively on food ethics in Harijan and Diet and Diet Reform

🧘 Fasting as Protest and Purification

Gandhi undertook 18 major fasts, including:

- Ahmedabad Mill Strike (1918) – 3 days

- Poona Pact (1932) – 6 days against separate Dalit electorates

- Noakhali riots (1947) – 4 days for communal harmony

- Final fast (1948) – 5 days, broken days before his assassination

He saw fasting as:

- A tool for self-purification

- A moral appeal to the conscience of oppressors

- A way to discipline the body and mind

⚖️ Criticism and Controversies

Despite his global reverence, Mahatma Gandhi faced intense criticism:

🧑🤝🧑 Caste and Dalit Rights

Gandhi opposed untouchability but supported the varna system. He clashed with B.R. Ambedkar over separate electorates for Dalits. Critics argue:

- He tried to reform, not abolish caste

- His term “Harijan” was patronizing

🌍 Early Racism in South Africa

In his early years, Gandhi made derogatory remarks about Black Africans, calling them “savages” and opposing their inclusion with Indians. Though he evolved later, these writings remain controversial.

🧘 Celibacy Experiments

His practice of sleeping beside young women to test his restraint was condemned by many, including Nehru and Western observers. Critics called it psychologically harmful and ethically questionable.

🕊️ Partition and Hindu-Muslim Relations

Gandhi’s insistence on communal harmony during Partition was seen by Hindu nationalists as appeasement. His support for Pakistan’s financial aid led to resentment, culminating in his assassination by Nathuram Godse in 1948.

🧭 Legacy of Personal Struggles

Mahatma Gandhi’s personal life was a tapestry of:

- Spiritual discipline

- Emotional complexity

- Ethical experimentation

- Unwavering simplicity

He was not a saint, but a seeker—flawed, introspective, and courageous. His struggles with family, sexuality, and criticism reveal a man constantly refining himself in pursuit of truth.

His motto, “My life is my message,” remains a challenge to every generation: to live with integrity, serve with humility, and question with courage.

Sources:

Why Do Some People Hate Gandhi – Knewspaper

Gandhi’s Celibacy Experiments – IndiaFacts

The Story of My Experiments with Truth – Wikipedia

Sevagram Ashram – Official Site

Sabarmati Ashram – House of MG

List of Gandhi’s Fasts – Wikipedia

Criticism of Gandhi – The Urban Herald

🔹 Part 7: Mahatma Gandhi’s Final Years – Martyrdom and Legacy

In his final years, Mahatma Gandhi stood not as a political strategist, but as the moral conscience of a nation. As India approached independence, Gandhi’s focus shifted from anti-colonial resistance to healing the wounds of communal hatred, guiding the soul of a divided country, and embodying the principles of nonviolence even in the face of betrayal. His assassination in 1948 marked the end of an era, but his legacy continues to shape global movements for justice, peace, and human dignity.

🕊️ Role in Partition and Communal Harmony

The announcement of India’s independence in 1947 was bittersweet. While the dream of Swaraj had been realized, it came at the cost of Partition, dividing the subcontinent into India and Pakistan. The decision, driven by political pressures and communal tensions, led to one of the largest and bloodiest migrations in history—over 15 million people displaced, and nearly a million killed in riots, massacres, and revenge attacks.

Mahatma Gandhi had opposed Partition from the beginning. He believed that Hindu-Muslim unity was essential for a free and just India. When Partition became inevitable, Gandhi did not retreat into despair. Instead, he became a peace pilgrim, walking through riot-torn areas in Noakhali (East Bengal) and Delhi, urging reconciliation.

In Noakhali, Gandhi:

- Walked barefoot through villages devastated by communal violence

- Stayed in Muslim homes to show solidarity

- Held daily prayer meetings promoting unity

- Refused security, saying, “I do not fear death. I fear hatred.”

In Delhi, he fasted to stop retaliatory violence against Muslims. His presence calmed tensions, and even militant groups paused their aggression. Gandhi’s actions were not political—they were deeply spiritual, rooted in his belief that India’s freedom was meaningless without communal harmony.

🧘 Last Fasts and Peace Missions

Between 1946 and 1948, Mahatma Gandhi undertook several fasts—not for political demands, but for moral healing.

🔹 Noakhali (1946)

After horrific riots in Bengal, Gandhi walked from village to village, preaching peace. He refused to leave until the violence stopped. His presence was transformative—many locals began rebuilding relationships across religious lines.

🔹 Calcutta (1947)

During Partition riots, Gandhi’s fast led to a miraculous ceasefire. Even Lord Mountbatten called it “the greatest miracle of modern times.” Gandhi’s moral authority was so profound that his silence could stop swords.

🔹 Delhi (January 1948)

Gandhi’s final fast was to demand:

- Protection of Muslims in Delhi

- Restoration of mosques

- Payment of ₹55 crore to Pakistan (as agreed during Partition)

Despite opposition, Gandhi stood firm. His fast lasted five days, and was broken only when leaders pledged to uphold peace. This act enraged Hindu extremists, who saw Gandhi as a traitor.

🔫 Assassination by Nathuram Godse (30 January 1948)

On 30 January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was walking to his evening prayer meeting at Birla House, New Delhi. At 5:17 PM, he was approached by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist who believed Gandhi had betrayed Hindus by appeasing Muslims.

Godse bowed, then fired three bullets into Gandhi’s chest. Gandhi collapsed, reportedly uttering “He Ram”—a final invocation of God.

The nation was stunned. Jawaharlal Nehru announced, “The light has gone out of our lives.” Gandhi’s death was not just the loss of a leader—it was the loss of India’s moral compass.

Godse was arrested, tried, and executed in 1949. His justification—that Gandhi’s nonviolence weakened Hindu interests—was condemned by the nation. Gandhi’s martyrdom became a symbol of sacrifice for peace.

🇮🇳 National Mourning and Global Tributes

India plunged into mourning. Millions wept. Shops closed. Flags flew at half-mast. Gandhi’s body was taken in a five-mile funeral procession through Delhi, followed by over two million people.

He was cremated at Raj Ghat, on the banks of the Yamuna River. Today, Raj Ghat remains a place of pilgrimage, marked by a simple black marble platform and an eternal flame.

Globally, tributes poured in:

- Albert Einstein said, “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.”

- Martin Luther King Jr. called Gandhi “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.”

- The United Nations declared October 2 (Gandhi’s birthday) as the International Day of Nonviolence.

Gandhi’s death was mourned not just in India, but in every corner of the world where justice and peace were cherished.

🌍 Mahatma Gandhi’s Legacy in India and Abroad

Gandhi’s legacy is vast and multifaceted. In India, he is revered as the Father of the Nation, but his influence extends far beyond borders.

🔹 In India

- Political Legacy: Gandhi’s principles shaped the Indian Constitution—especially its emphasis on secularism, equality, and nonviolence.

- Social Reform: His campaigns against untouchability, caste discrimination, and communal hatred laid the groundwork for modern social justice movements.

- Economic Vision: Gandhi’s emphasis on Khadi, village industries, and self-reliance inspired rural development programs and the cooperative movement.

- Cultural Impact: His life is commemorated in museums, memorials, and educational curricula. Places like Sabarmati Ashram, Sevagram, and Gandhi Smriti preserve his legacy.

🔹 Globally

- Civil Rights Movements: Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha inspired leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and César Chávez.

- Peace Advocacy: His teachings are studied in conflict resolution, diplomacy, and peacebuilding.

- Environmentalism: Gandhi’s emphasis on simplicity and sustainability resonates with modern ecological movements.

- Human Rights: His belief in dignity for all continues to influence global human rights discourse.

🧑🏾🤝🧑🏿 Influence on Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela

🔹 Martin Luther King Jr.

King discovered Gandhi’s teachings during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He said, “Christ gave us the goals, Gandhi gave us the tactics.” King adopted:

- Nonviolent protest

- Civil disobedience

- Spiritual discipline

He visited India in 1959, calling it “a pilgrimage.” Gandhi’s influence shaped the American civil rights movement, from the Selma marches to the I Have a Dream speech.

🔹 Nelson Mandela

Mandela initially supported armed resistance against apartheid. But after years in prison, he embraced Gandhi’s methods. He said, “Gandhi’s nonviolence was not cowardice—it was courage.”

Mandela’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, peaceful transition of power, and emphasis on forgiveness were deeply Gandhian. South Africa honors Gandhi with statues, museums, and educational programs.

🧭 Additional Reflections: Gandhi’s Enduring Relevance

Even decades after his death, Mahatma Gandhi remains relevant:

- In Ukraine, peace activists invoke his name.

- In climate protests, his simplicity is a model.

- In digital age debates, his truth-seeking offers clarity.

Gandhi’s life reminds us that:

- Power without ethics is hollow

- Freedom without compassion is dangerous

- Change begins with the individual

His message is timeless: “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

🕯️ Conclusion: A Life That Became a Message

Mahatma Gandhi’s final years were a testament to his unwavering commitment to truth, nonviolence, and human dignity. He chose peace over politics, love over hatred, and sacrifice over safety.

His assassination was not the end—it was the beginning of a legacy that continues to inspire. Gandhi’s life was his message, and that message still echoes in every corner of the world where people fight for justice without violence.

Sources:

Gandhi’s Legacy in India – Ease India Trip

Gandhi’s Influence on MLK and Mandela – Indian Express

🔹 Who Gave Mahatma Gandhi the Title of “Rashtrapita” (Father of the Nation) and Why He Deserved It

Mahatma Gandhi was first called “Rashtrapita” (Father of the Nation) by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in a radio address on 6 July 1944. This symbolic title was never officially conferred by the Indian government due to constitutional limitations, but it became deeply embedded in India’s collective consciousness. Gandhi earned this honor through his unmatched leadership in India’s freedom struggle, his moral authority, and his ability to unite millions through truth and nonviolence.

🗣️ The Origin of the Title “Rashtrapita”

The term “Rashtrapita” was first publicly used by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, leader of the Azad Hind Fauj (Indian National Army), during a radio broadcast from Singapore on 6 July 1944. At the time, Mahatma Gandhi was imprisoned in India, mourning the death of his wife Kasturba Gandhi, and suffering from poor health.

In his emotional message, Bose said:

“Father of our Nation, in this holy war of India’s liberation, we ask for your blessings and good wishes.”

This was not a political statement—it was a heartfelt tribute from one revolutionary to another. Despite ideological differences, Bose recognized Gandhi’s spiritual leadership and his role as the guiding light of India’s independence movement.

📜 Why the Title Was Never Officially Conferred

Although Gandhi is universally referred to as the “Father of the Nation,” no formal government resolution or constitutional order has ever granted him this title. This is due to Article 18(1) of the Indian Constitution, which prohibits the state from conferring titles except for academic or military distinctions.

In fact, multiple Right to Information (RTI) queries have confirmed that:

- There is no official record of Gandhi being legally designated as “Rashtrapita.”

- The title remains honorific and symbolic, not constitutional.

Yet, the absence of legal recognition has not diminished the reverence associated with the term. Gandhi’s legacy transcends bureaucracy—it lives in the hearts of millions.

🇮🇳 Why Mahatma Gandhi Deserved the Title “Rashtrapita”

1. Leadership Through Nonviolence

Gandhi pioneered Satyagraha, a philosophy of nonviolent resistance rooted in truth and moral courage. He led:

- The Champaran Satyagraha (1917) for indigo farmers

- The Kheda movement (1918) for tax relief

- The Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–22)

- The Salt March (1930)

- The Quit India Movement (1942)

Each campaign mobilized millions without violence. Gandhi proved that moral force could defeat imperial power.

2. Uniting a Diverse Nation

India is a mosaic of languages, religions, and castes. Gandhi united:

- Hindus and Muslims through communal harmony efforts

- Dalits and upper castes through anti-untouchability campaigns

- Urban elites and rural peasants through Khadi and Swadeshi

He made nationalism inclusive, not elitist. His mass appeal made him the symbolic father of a united India.

3. Spiritual and Ethical Authority

Gandhi’s life was his message. He practiced:

- Celibacy and simplicity

- Manual labor and self-reliance

- Truthfulness and humility

He lived in Ashrams, wore Khadi, and ate simple food. His moral discipline inspired trust and devotion. Even critics acknowledged his spiritual stature.

4. Sacrifice and Suffering

Gandhi was imprisoned multiple times, fasted for peace, and endured personal loss. He:

- Lost Kasturba in prison (1944)

- Fasted during communal riots in Noakhali and Delhi

- Was assassinated in 1948 while walking to prayer

His martyrdom sealed his place as the Father of the Nation. He gave his life for India’s soul.

🤝 Subhas Chandra Bose and Gandhi: A Complex Relationship

It’s significant that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, a leader known for armed resistance, was the one to call Gandhi “Rashtrapita.” Their relationship was marked by:

- Ideological differences: Bose favored military action; Gandhi insisted on nonviolence.

- Mutual respect: Despite disagreements, Bose admired Gandhi’s moral leadership.

- Strategic unity: Bose sought Gandhi’s blessings for the Azad Hind Fauj.

By calling Gandhi “Rashtrapita,” Bose acknowledged that Gandhi’s moral authority transcended political tactics.

🧭 Legacy of the Title “Rashtrapita”

Even without legal sanction, the title “Rashtrapita” has become:

- Embedded in textbooks, speeches, and memorials

- Used by leaders like Nehru, Patel, and Tagore

- Celebrated on Gandhi Jayanti (2 October), now the International Day of Nonviolence

Gandhi’s image is on Indian currency, his teachings are in school curricula, and his life is studied worldwide. The title reflects India’s emotional and cultural reverence, not just political recognition.

🌍 Global Recognition of Gandhi’s Role

Gandhi’s influence extends beyond India:

- Martin Luther King Jr. adopted Satyagraha in the U.S. civil rights movement.

- Nelson Mandela credited Gandhi for shaping South Africa’s peaceful transition.

- UNESCO and the UN honor Gandhi’s legacy in peace education.

His title as “Father of the Nation” is echoed globally as a symbol of ethical leadership.

🕯️ Conclusion: A Title Earned by Life, Not Law

Mahatma Gandhi was called “Rashtrapita” not by decree, but by devotion. Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s tribute in 1944 captured what millions felt: that Gandhi was not just a leader, but a moral father, a spiritual guide, and the soul of India’s freedom.

He deserved the title because:

- He led without violence

- He united without force

- He sacrificed without demand

- He lived what he preached

In the words of Nehru, “The Father of the Nation is no more.” But in truth, Rashtrapita lives on—in every act of peace, every voice of justice, and every dream of freedom.

Sources:

- Jagran Hindi News – Who Called Gandhi Rashtrapita

- IndiaTV – Did Gandhi Ever Get a Formal Title

- Sage Advices – Who Gave the Title of Rashtrapita

🔚 Conclusion: “Rashtrapita”—A Title Forged in Sacrifice, Not Sanction

The title “Rashtrapita”, first spoken by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in 1944, was not granted by law—it was bestowed by history. It did not emerge from a government resolution, but from the collective reverence of a nation that saw in Mahatma Gandhi its moral compass, its spiritual guide, and its most selfless leader.

Gandhi never held formal office. He never commanded armies. Yet he led millions—through silence and salt, through spinning wheels and satyagraha, through fasts and forgiveness. His leadership was not transactional; it was transformational.

He deserved the title “Rashtrapita” because:

- He fathered a revolution of conscience, not conquest.

- He nurtured a fractured nation, not with power, but with principle.

- He sacrificed his comforts, his family, and ultimately his life for the soul of India.

Even those who disagreed with him—like Bose—recognized that Gandhi’s influence transcended ideology. His legacy was not confined to political victories, but to the awakening of a people.

Though the Indian Constitution prohibits official titles, the absence of legal recognition only amplifies the emotional truth: Gandhi is our Rashtrapita—not by decree, but by devotion.

In every village spinning Khadi, in every citizen choosing peace over violence, in every movement that seeks justice through truth—Gandhi lives on. His life was his message. And that message still echoes:

Lead with love. Resist with courage. Serve with humility.

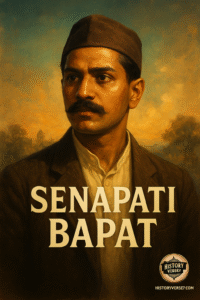

Internal Links: 1.https://historyverse7.com/bal-gangadhar-tilak/ 2.https://historyverse7.com/ram-prasad-bismil/

📘 FAQ: Mahatma Gandhi as Rashtrapita

1. Who first called Mahatma Gandhi the “Father of the Nation”?

Answer:

The title “Rashtrapita” was first publicly used by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in a radio broadcast from Singapore on 6 July 1944. Despite ideological differences, Bose addressed Gandhi with deep reverence, saying:

“Father of our Nation, in this holy war of India’s liberation, we ask for your blessings and good wishes.”

This emotional tribute from one revolutionary to another cemented Gandhi’s place as the moral leader of India.

2. Is “Rashtrapita” an official title recognized by the Indian government?

Answer:

No, the title “Rashtrapita” is not officially recognized by the Indian Constitution. Article 18 prohibits the state from conferring titles except for military or academic distinctions. However, Gandhi’s designation as “Father of the Nation” is universally accepted in India and abroad as a symbolic honor, rooted in public sentiment and historical reverence.

3. Why did Mahatma Gandhi deserve the title “Rashtrapita”?

Answer:

Gandhi earned the title through:

Nonviolent leadership in India’s freedom struggle

Spiritual discipline and ethical living

Unity across caste, religion, and class

Sacrifice, including imprisonment, fasting, and ultimately martyrdom

He didn’t just lead India to independence—he awakened its soul. His life was his message, and that message continues to guide generations.

4. Did Mahatma Gandhi accept the title “Father of the Nation”?

Answer:

Gandhi never formally accepted or promoted the title. True to his humility, he often deflected praise and insisted that the people were the real heroes of the freedom movement. Yet, he acknowledged the emotional weight of the term when used by leaders like Bose, understanding that it reflected love, not power.

5. How does Gandhi’s legacy as “Rashtrapita” influence the world today?

Answer:

Gandhi’s legacy transcends borders. His philosophy of Satyagraha inspired:

Martin Luther King Jr. in the U.S. civil rights movement.

Nelson Mandela in South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle.

César Chávez in labor rights activism

Globally, Gandhi is seen as a symbol of ethical leadership, peaceful resistance, and human dignity. His title “Rashtrapita” is not just India’s—it’s the world’s tribute to a life lived in service of truth.

Share this content:

The Soul of India’s Freedom.

🔥👍👍

He sacrificed his comforts, his family, and ultimately his life for the soul of India….nice 👍🏻🚩